Spring Cloud Netflix Eureka - The Hidden Manual

IntroductionPermalink

In 2015-2016, we redesigned a monolithic application into Microservices and chose the Spring Cloud Netflix as the foundation.

Quoting the docs:

(Spring Cloud Netflix) provides Netflix OSS integrations for Spring Boot apps through autoconfiguration and binding to the Spring Environment and other Spring programming model idioms.

Overtime, we gained more familiarity with the framework, and I even contributed some pull requests. I thought I knew enough until I started looking into Eureka redundancy and failover. A quick proof of concept didn’t work and as I dug more, I came across other poor souls scouring the internet for similar information. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much to find. To their credit, the Spring Cloud documentation is fairly good, and there’s also a Netflix Wiki, but none went into the level of detail I was looking for. This post attempts to bridge that gap. I assume some basic familiarity with Eureka and service discovery, so if you’re new to those, come back after having read the Spring Cloud documentation.

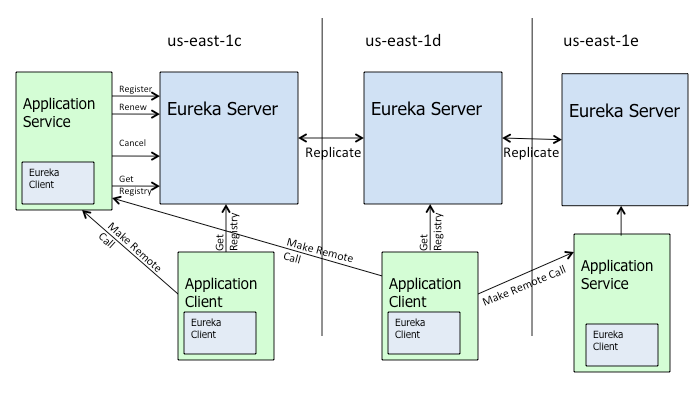

Basic ArchitecturePermalink

Eureka has two basic components, server and client. Quoting the Netflix Wiki:

Eureka is a REST (Representational State Transfer) based service that is primarily used in the AWS cloud for locating services for the purpose of load balancing and failover of middle-tier servers. We call this service, the Eureka Server. Eureka also comes with a Java-based client component, the Eureka Client, which makes interactions with the service much easier. The client also has a built-in load balancer that does basic round-robin load balancing.

A Eureka client application is referred to as an instance. There’s a subtle difference between a client application and Eureka client; the former is your application while the latter is a component provided by the framework.

Netflix designed Eureka to be highly dynamic. There are properties, and then there are properties that define intervals after which to look for changes in the first set of properties. This is a common paradigm, meaning most of these properties can be changed at runtime, and are picked up in the next refresh cycle. For example, the URL that the client uses to register with Eureka can change and that is picked up after 5min (configurable by eureka.client.eurekaServiceUrlPollIntervalSeconds). Most users will not need such dynamic updates but if you do, you can find all the configuration options as follows:

- For Eureka server config:

org.springframework.cloud.netflix.eureka.server.EurekaServerConfigBeanthat implementscom.netflix.eureka.EurekaServerConfig. All properties are prefixed byeureka.server. - For Eureka client config:

org.springframework.cloud.netflix.eureka.EurekaClientConfigBeanthat implementscom.netflix.discovery.EurekaClientConfig. All properties are prefixed byeureka.client. - For Eureka instance config:

org.springframework.cloud.netflix.eureka.EurekaInstanceConfigBeanthat implements (indirectly)com.netflix.appinfo.EurekaInstanceConfig. All properties are prefixed byeureka.instance.

Refer to Netflix Wiki for further architectural details.

Eureka Instance and ClientPermalink

An instance is identified in Eureka by the eureka.instance.instanceId or, if not present, eureka.instance.metadataMap.instanceId. The instances find each other using eureka.instance.appName, which Spring Cloud defaults to spring.application.name or UNKNOWN, if the former is not defined. You’ll want to set spring.application.name because applications with the same name are clustered together in Eureka server. It’s not required to set eureka.instance.instanceId, as it defaults to CLIENT IP:PORT, but if you do set it, it must be unique within the scope of the appName. There’s also a eureka.instance.virtualHostName, but it’s not used by Spring, and is set to spring.application.name or UNKNOWN as described above.

If registerWithEureka is true, an instance registers with a Eureka server using a given URL; then onwards, it sends heartbeats every 30s (configurable by eureka.instance.leaseRenewalIntervalInSeconds). If the server doesn’t receive a heartbeat, it waits 90s (configurable by eureka.instance.leaseExpirationDurationInSeconds) before removing the instance from registry and there by disallowing traffic to that instance. Sending heartbeat is an asynchronous task; if the operation fails, it backs off exponentially by a factor of 2 until a maximum delay of eureka.instance.leaseRenewalIntervalInSeconds * eureka.client.heartbeatExecutorExponentialBackOffBound is reached. There is no limit to the number of retries for registering with Eureka.

The heartbeat is not the same as updating the instance information to the Eureka server. Every instance is represented by an com.netflix.appinfo.InstanceInfo, which is a bunch of information about the instance. The InstanceInfo is sent to the Eureka server at regular intervals, starting at 40s after startup (configurable by eureka.client.initialInstanceInfoReplicationIntervalSeconds), and then onwards every 30s (configurable by eureka.client.instanceInfoReplicationIntervalSeconds).

If eureka.client.fetchRegistry is true, the client fetches the Eureka server registry at startup and caches it locally. From then on, it only fetches the delta (this can be turned off by setting eureka.client.shouldDisableDelta to false, although that’d be a waste of bandwidth). The registry fetch is an asynchronous task scheduled every 30s (configurable by eureka.client.registryFetchIntervalSeconds). If the operation fails, it backs off exponentially by a factor of 2 until a maximum delay of eureka.client.registryFetchIntervalSeconds * eureka.client.cacheRefreshExecutorExponentialBackOffBound is reached. There is no limit to the number of retries for fetching the registry information.

The client tasks are scheduled by com.netflix.discovery.DiscoveryClient, which Spring Cloud extends in org.springframework.cloud.netflix.eureka.CloudEurekaClient.

Why Does It Take So Long to Register an Instance with Eureka?Permalink

Mostly copied from spring-cloud-netflix#373 with my own spin put on it.

-

Client Registration

The first heartbeat happens 30s (described earlier) after startup so the instance doesn’t appear in the Eureka registry before this interval.

-

Server Response Cache

The server maintains a response cache that is updated every 30s (configurable by

eureka.server.responseCacheUpdateIntervalMs). So even if the instance is just registered, it won’t appear in the result of a call to the/eureka/appsREST endpoint. However, the instance may appear on the Eureka Dashboard just after registration. This is because the Dashboard bypasses the response cache used by the REST API. If you know the instanceId, you can still get some details from Eureka about it by calling/eureka/apps/<appName>/<instanceId>. This endpoint doesn’t make use of the response cache.So, it may take up to another 30s for other clients to discover the newly registered instance.

-

Client Cache Refresh

Eureka client maintain a cache of the registry information. This cache is refreshed every 30s (described earlier). So, it may take another 30s before a client decides to refresh its local cache and discover other newly registered instances.

-

LoadBalancer Refresh

The load balancer used by Ribbon gets its information from the local Eureka client. Ribbon also maintains a local cache to avoid calling the client for every request. This cache is refreshed every 30s (configurable by

ribbon.ServerListRefreshInterval). So, it may take another 30s before Ribbon can make use of the newly registered instance.In the end, it may take up to 2min before a newly registered instance starts receiving traffic from the other instances.

Eureka ServerPermalink

The Eureka server has a peer-aware mode, in which it replicates the service registry across other Eureka servers, to provide load balancing and resiliency. Peer-aware mode is the default so a Eureka server also acts as a Eureka client and registers to a peer on a given URL. This is how you should run Eureka in production but for demo or proof of concepts, you can run in standalone mode by setting registerWithEureka to false.

When the eureka server starts up it tries to fetch all the registry information from the peer eureka nodes. This operation is retried 5 times for each peer (configurable by eureka.server.numberRegistrySyncRetries). If for some reason this operation fails, the server does not allow clients to get the registry information for 5min (configurable by eureka.server.getWaitTimeInMsWhenSyncEmpty).

Eureka peer awareness brings in a whole new level of complication by introducing a concept called “self-preservation” (can be turned off by setting eureka.server.enableSelfPreservation to false). In fact, when looking online, this is where I saw most people tripping on. From Netflix Wiki:

When the Eureka server comes up, it tries to get all of the instance registry information from a neighboring node. If there is a problem getting the information from a node, the server tries all of the peers before it gives up. If the server is able to successfully get all of the instances, it sets the renewal threshold that it should be receiving based on that information. If any time, the renewals falls below the percent configured for that value, the server stops expiring instances to protect the current instance registry information.

The math works like this: If there are two clients registered to a Eureka instance, each one sending a heartbeat every 30s, the instance should receive 4 heartbeats in a minute. Spring adds a lower minimum of 1 to that (configurable by eureka.instance.registry.expectedNumberOfRenewsPerMin), so the instance expects to receive 5 heartbeats every minute. This is then multiplied by 0.85 (configurable by eureka.server.renewalPercentThreshold) and rounded to the next integer, which brings us back to 5 again. If anytime there are less than 5 heartbeats received by Eureka in 15min (configurable by eureka.server.renewalThresholdUpdateIntervalMs), it goes into self-preservation mode and stops expiring already registered instances.

Eureka server makes an implicit assumption that the clients are sending their heartbeat at a fixed rate of 1 every

30s. If two instances are registered, the server expects to receive (2 * 2 + 1 ) * 0.85 = 5 heartbeats every minute.

If the renewal rate drops below this value, the self-preservation mode is activated. Now, if the clients are sending heartbeats much faster (say, every 10s), the server receives 12 heartbeats per minute and keeps receiving 6/min even if

one of the instances goes down. Thus, the self protection mode is not activated even though it should be. This is why

it’s not advisable to change eureka.client.instanceInfoReplicationIntervalSeconds. You can instead tinker with eureka.server.renewalPercentThreshold if you must.

Eureka peers don’t count towards the expected number of renewals, but the heartbeats from them is considered within the number of renewals received last minute. In peer-aware mode, the heartbeats can go to any Eureka instance; this is important when running behind a load balancer or as a Kubernetes service, where the heartbeats are sent in Round-robin mode (usually) to each instance.

The Eureka server doesn’t come out of self-preservation mode until the renewals rise above the threshold. This may cause the clients to get the instances that do not exist anymore. Refer to Understanding Eureka Peer to Peer Communication

One more thing: There is a gotcha with running more than one Eureka server on the same host. Netflix code (com.netflix.eureka.cluster.PeerEurekaNodes.isThisMyUrl) filters out the peer URLs that are on the same host. This may have been done to prevent the server registering as its own peer (I’m guessing here) but because they don’t check for the port, peer awareness doesn’t work unless the Eureka hostnames in the eureka.client.serviceUrl.defaultZone are different. The hacky workaround for this is to define unique hostnames and then map them to 127.0.0.1 in the /etc/hosts file (or its Windows equivalent). Spring Cloud doc talks about this workaround but fails to mention why it’s needed. Now you know.

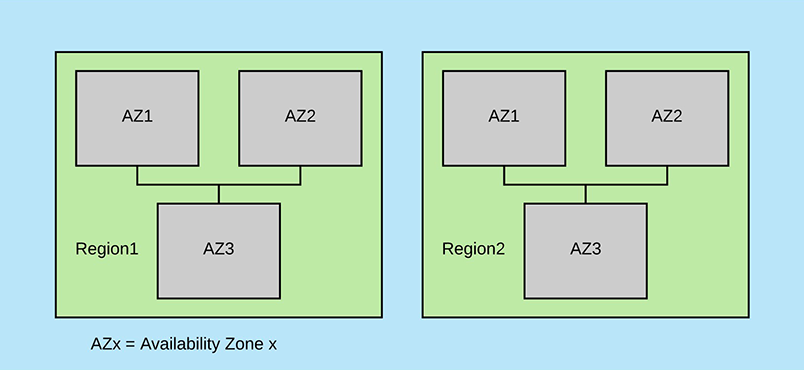

Regions and Availability ZonesPermalink

Eureka was designed to run in AWS and uses many concepts and terminologies that are specific to AWS. Regions and Zones are two such things. From AWS doc:

Amazon EC2 is hosted in multiple locations world-wide. These locations are composed of regions and Availability Zones. Each region is a separate geographic area. Each region has multiple, isolated locations known as Availability Zones … Each region is completely independent. Each Availability Zone is isolated, but the Availability Zones in a region are connected through low-latency links.

The Eureka dashboard displays the Environment and Data center. The values are set to test and default, respectively, from org.springframework.cloud.netflix.eureka.server.EurekaServerBootstrap by using com.netflix.config.ConfigurationManager. There are various lookups and fallbacks, so if for some reason you need to change those, refer to the source code of the aforementioned classes.

The Eureka client prefers the same zone by default (configurable by eureka.client.preferSameZone). From com.netflix.discovery.endpoint.EndpointUtils.getServiceUrlsFromDNS Javadoc:

Get the list of all eureka service urls from DNS for the eureka client to talk to. The client picks up the service url from its zone and then fails over to other zones randomly. If there are multiple servers in the same zone, the client once again picks one randomly. This way the traffic will be distributed in the case of failures.

Ticket spring-cloud-netflix#203 is open as of this writing where several people talk about regions and zones. I’ve not verified any of that so I can’t comment on how regions and zones work with Eureka.

High Availability (HA)Permalink

Mostly copied from spring-cloud-netflix#203 with my own spin put on it.

- The HA strategy seems to be one main Eureka server (

server1) with backup(s) (server2). - A client is provided with a list of Eureka servers through config (or DNS or

/etc/hosts) - Client attempts to connect to

server1; at this point,server2is sitting idle. - In case

server1is unavailable, the client tries the next one from the list. - When

server1comes back online, client goes back to usingserver1.

Of course server1 and server2 can be ran in peer-aware mode, and their registries replicated. But that’s orthogonal to client registration.

Leave a comment